(1793 - 1867)

Return to either Home page, Edward Goodall or Frederick Goodall.

The following is by Ken Watson, a descendant of Clarkson Stanfield

Reference: http://www.rideau-info.com/ken/genealogy/stanfield/index.html

Clarkson Stanfield was my g-g-g-grandfather. He was father to George Clarkson Stanfield, my g-g-grandfather, who was father to Edward John Clarkson Stanfield, my great-grandfather, who was father to Edythe Frances Stanfield, my grandmother. The full linealogy can be found on my

Stanfield Page.

My thanks to my sister Mary for sending me the pictures shown on this page, a copy of Charles Dickens, by Edgar Johnson from which much of the Dickens information was obtained, and for generally being persistent in tracking down information about our ancestor - "dear old Stanny".

Updates and corrections to this page were provided with the help of Pietre van der Merwe (per comm), and the book "The Spectacular Career of Clarkson Stanfield" put together by Pietre for the Tyne and Wear County Council Museums, 1979.

- Ken Watson, 1998

(1793 - 1867)

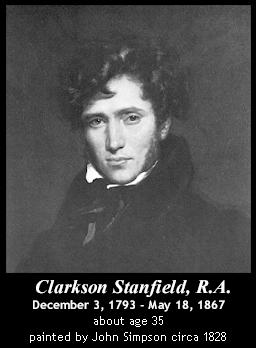

Clarkson Frederick Stanfield (sometimes erroneously called "William Clarkson Stanfield"), was born on December 3, 1793 in Sunderland, England. His parents were James Field Stanfield (1747-1824) and Mary Hoad. Clarkson was the fifth (and youngest) son of this marriage. His mother, Mary, died in 1801 and his father re-married, to Maria Kell, a year later.

Clarkson Frederick Stanfield (sometimes erroneously called "William Clarkson Stanfield"), was born on December 3, 1793 in Sunderland, England. His parents were James Field Stanfield (1747-1824) and Mary Hoad. Clarkson was the fifth (and youngest) son of this marriage. His mother, Mary, died in 1801 and his father re-married, to Maria Kell, a year later.

His father, James Field Stanfield, was Irish, born in Dublin. James studied for the priesthood in France, but gave that up, moved to Liverpool and worked on a ship engaged in the slave trade. He was so horrified by this experience that he quit the sea, joined the ranks of the abolitionists, and became an actor, playwright and author.

Clarkson's mother, Mary Hoad, was an actress and an artist. She taught painting and got Clarkson started on his lifelong career.

As a young boy, Clarkson was apprenticed to a Heraldic painter in Edinburgh, but after two years he left and went to sea in a merchant ship at the age of fifteen (1808). In 1812, he was pressed into the navy. During his time in the navy he used the alias "Roderick Bland". After an accident, (a fall from the rigging of the ship) left him unfit for service he was discharged from the Navy in December, 1814. In 1815 he sailed on the merchant ship Warley for China. He returned a year later. He was supposed to set sail on another merchant ship but it never sailed. In need of work, he started on a new career of theatre scene painter in east London. Clarkson had done painting throughout his naval career, doing up theatre scenes for some naval productions as well as some painting and sketches. Now, in mid-1816, this became his sole work.

Shortly after starting his career as a scene painter, he started a family. In July, 1818 he married his first wife, Mary Hutchinson. They had two children, Clarkson William and Mary Elizabeth. Mary Hutchinson died in 1821, about a month after the birth of Mary Elizabeth. His second marriage was to Rebecca Adcock in about late 1824, early 1825. They had 10 children; Henry, George, James, John, Francis, Raymond, Harriet, Rebecca, Field, and Edward. The second son, George Clarkson Stanfield, born on May 1, 1828, was a pupil of his father, and painted the same class of subjects. George Clarkson is sometimes confused in the artistic literature for his father Clarkson. George exhibited seventy-three at the Royal Academy, and forty-nine at the British Institution from 1844 to 1876. He died in 1878.

Clarkson's career continued to flourish as he worked in theatres in London and Edinburgh. He became known not only for the quality of his work, but for his endurance and the speed at which he worked. At the same time he began to paint small marines in oil and met his great friend and sometimes rival, David Roberts, R.A. (1796-1864). In 1823, both he and Roberts were hired as scene painters for Drury Lane, a theatre illuminated by the new medium of gas lighting. A review in the December 27th, 1828 edition of The Times best summarizes Stanfield's work:

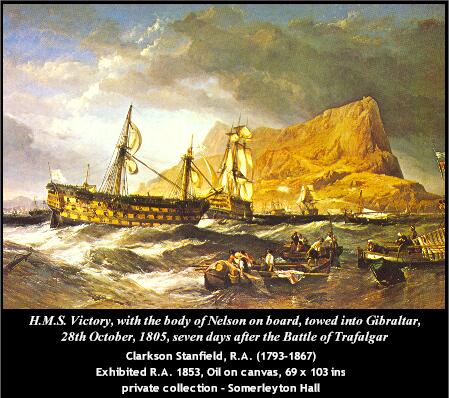

"When our memory glances back a few years and we compare in "the mind's eye", the dingy, filthy scenery which was exhibited here - trees, like inverted mops, of a brick-dust hue - buildings generally at war with perspective - water as opaque as the surrounding rocks, and clouds not a bit more transparent - when we compare these things with what we now see, the alteration strikes us as nearly miraculous. This is mainly owing to Mr. Stanfield. To the effective execution of the duties belonging to the scenic department, he brought every necessary qualification - a knowledge of light and shade which enabled him to give to his scenes great transparency and a ready and judicious taste for composition, whether landscape, architecture or coast, but more especially for the last . . . His present scene is fully equal - in some parts superior - to any thing he has heretofore done ... The view of Lord Nelson's ship the Victory, is the most gorgeous specimen of naval architectural painting that we ever saw ... The view of Gibraltar, bristling with fortifications is uncommonly fine. It exhibits an extent of space ... and a grandeur of elevation which seem to say "I am invulnerable"."

As his scene painting career blossomed, Clarkson did not neglect his easel painting. He first exhibited in 1820, and was recognised as a marine painter of great promise. He was one of the founders of the Society of British Artists in 1823, becoming its President in 1829, the same year he sent his first picture to the Royal Academy. He was elected Associate of the Royal Academy and a Royal Academician in 1832 and 1835. In late 1834 he resigned as scene painter for Drury Lane and devoted most of his time to easel pictures. He never left scene painting entirely, though most of his later work was done for friends.

As his scene painting career blossomed, Clarkson did not neglect his easel painting. He first exhibited in 1820, and was recognised as a marine painter of great promise. He was one of the founders of the Society of British Artists in 1823, becoming its President in 1829, the same year he sent his first picture to the Royal Academy. He was elected Associate of the Royal Academy and a Royal Academician in 1832 and 1835. In late 1834 he resigned as scene painter for Drury Lane and devoted most of his time to easel pictures. He never left scene painting entirely, though most of his later work was done for friends.

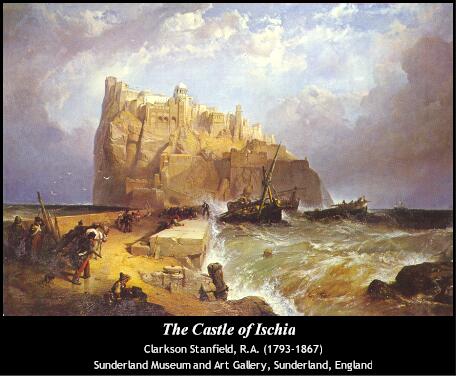

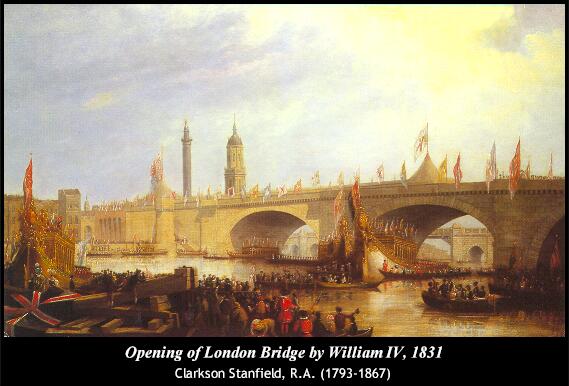

Painting in both oil and watercolour he specialised in shipping, coastal and river scenes, making regular visits to Italy, France and Holland and painting many Venetian views in the 1830s and Dutch scenes in the 1840s. He was commissioned to paint the opening of the New London Bridge and Portsmouth Harbour by King William IV, but probably his finest work was the Battle of Trafalgar in 1836, painted for the United Services Club in Pall Mall, London, where it still hangs to this very day. Other important works included The Castle of Ischia (1841), The Day After the Wreck (1844), On the Dogger Bank (1846), The Battle of Roveredo (1851), Victory towed into Gibraltar (1853), and The abandoned (1856).

Clarkson Stanfield is regarded as one of England's finest marine painters, and to Ruskin he was "the leader of the English realists". He was held in great esteem, and no artist could have shown more knowledge of ships and sea conditions. He was considered Turner's nearest rival as a delineator of cloud forms. He excelled at scene painting which at the time was held in much lower esteem than easel painting. Critics of his works often refer to some of the scene techniques he used in his easel works. But for Stanfield these had a purpose. He would often paint with brighter, more brilliant colours knowing that over time the paint colours would fade, and in fact noted that he preferred to look at his paintings some years after they were first painted when the colours had time to mellow.

Much of his work was a result of his many travels abroad. While travelling, he would make an extensive number of sketches. Later he would use these in his studio to produce his oils and watercolours. Rarely did he do an oil or watercolour from life. Stanfield was meticulous in organizing his sketches keeping them numbered and ordered. His first tour was to Italy in 1824 with William Brockedon. After several short trips to France he did a major trip to Venice, via Germany, Switzerland and Austria, in 1830. The next 10 years included more trips to Germany and Italy. In 1843 he toured Holland and in 1851 he toured France and Spain with his wife, Rebecca. He built up an extensive collection of sketches from these trips and would often take delight in using them to recount his journeys to visitors.

He died in Hampstead on May 18, 1867 after 10 years of poor health. His works are today represented in many English Collections and Galleries, including the British Museum and the Victorian and Albert Museum in London. His Studio sale was held at Christie's on the 8th May 1868.

Clarkson was a good natured man with a sense of humour. One of his best friends was Charles Dickens who he met in 1837 when he was 42 and Dickens was 24. They remained great friends until Stanfield's death in 1867 with Dickens being one of the last visitors that Stanfield saw on the day he died. After Clarkson's death, Dickens wrote: "He was the soul of frankness, generosity and simplicity. The most genial, the most affectionate, the most loving and the most lovable of men. Success had never for an instant spoiled him . . . He had been a sailor once; and all the best characteristics that are popularly attributed to sailors, being his, and being in him refined by the influence of his Art, formed a whole not likely to be often seen."

Another insight into Clarkson's character is another quote from Dickens in a letter he wrote to Cornelius Felton regarding a trip to Cornwall in 1842 that he, John Forster, Daniel Maclise and Clarkson Stanfield took:

- "Blessed star of morning! Such a trip as we had into Cornwall just after Longfellow went away! . . .Heavens! if you could have seen the necks of bottles, distracting in their immense variety of shape, peering out of the carriage pockets! If you could have witnessed the deep devotion of the postboys, the maniac glee of the waiters! If you could have followed us into the earthy old churches we visited, and into the strange caverns on the gloomy sea-shore, and down into the depths of mines, and up to the tops of giddy heights, where the unspeakably green water was roaring, I don't know how many hundred feet below! . . . I never laughed in my life as I did on this journey. It would have done you good to hear me. I was choking and gasping and bursting the buckle off the back of my stock, all the way. And Stanfield got into such apoplectic entanglements that we were obliged to beat him on the back with portmanteaus before we could recover him."

Dickens contemplated producing a play that was to be written by Collins about the ill fated arctic expedition of Sir John Franklin. "The next afternoon Stanfield dropped in at Tavisstock House, and on hearing about the play became immensely excited. He upset the school room Dickens had straightened out by dragging chairs to represent the proscenium and outlining the scenery with walking sticks." Stanfield ended up painting the scenery for the second and third acts of "The Frozen Deep". (Dickens later took these scenes and transformed them into wall decorations for his house).

In a letter to Stanfield's son, George, after Clarkson's death Dickens wrote "No one of your father's friends can ever have loved him more dearly than I always did, or can have better known the worth of his noble character." Letter to George Stanfield, May 19, 1867. A volume of the letters exchanged between Dickens and Stanfield was published after Stanfield's death, and only two copies are now known to still exist. One of these is at the Dickens Museum in London.

Stanfield had his serious side too. In the early 1840s he was becoming more religious, moving towards Catholicism. This was perhaps brought on by the death of his oldest son from his second marriage, Henry, at age 11 in 1838. His conversion of Catholicism caused some friction in the family, particularly with his oldest son from his first marriage (Clarkson William). On October 3, 1846, Clarkson was baptized or re-baptized with the names Thomas Clarkson, after his original namesake, the Reverend Thomas Clarkson who had died the week before. His friends at the time still very much enjoyed Clarkson's company, but learned to avoid discussions relating to religious matters.

Stanfield had his serious side too. In the early 1840s he was becoming more religious, moving towards Catholicism. This was perhaps brought on by the death of his oldest son from his second marriage, Henry, at age 11 in 1838. His conversion of Catholicism caused some friction in the family, particularly with his oldest son from his first marriage (Clarkson William). On October 3, 1846, Clarkson was baptized or re-baptized with the names Thomas Clarkson, after his original namesake, the Reverend Thomas Clarkson who had died the week before. His friends at the time still very much enjoyed Clarkson's company, but learned to avoid discussions relating to religious matters.

Clarkson was a family man, particularly devoted to his second wife, Rebecca Adcock who was noted as having a powerful and somewhat forbidding personality. She converted to Catholicism at the same time as Clarkson. When Clarkson was travelling, he looked forward to receiving a letter from Rebecca almost every day and could get quite upset if one did not arrive.

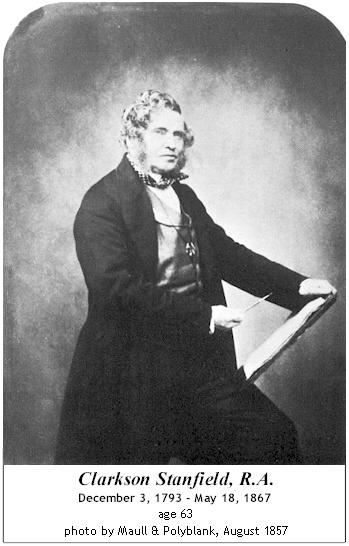

His friends all remembered Stanfield as a good natured man full of humour. He was noted as being a "good-humoured listener to more dynamic conversationalists, rarely asserted himself and when he spoke 'said his little with his usual modesty' (Macready)." He grew at tad portly as he entered late middle-age and was once noted as having a "jolly red sailor face beaming with excitement and delight" (Charles Dickens Jr.). In his last 10 years his health, which had never been that good, deteriorated. His rheumatism and bad leg often kept him housebound and there were long periods in which he was unable to work. The sudden death of David Roberts in 1864 seems to have deeply affected him. However, he kept painting, right up to the end, even after doctors ordered him to stop painting large oils. When he died on May 18, 1867, there was an unfinished painting on his easel and a previous work, A Skirmish off Heligoland hanging in the Royal Academy exhibition.

![]()

Clarkson exhibited his works between 1820 and1867 and these included; 135 R.A., 22 B.I..and 21 S.S.

In the National Gallery of British Art (Vernon Collection) are four of Stanfield's pictures, 'Entrance to the Zuyder Zee, Texel Island', 'The Lake of Como', 'The Canal of the Giudecca and Church of the Jesuits, Venice' and a sketch for 'The Battle of Trafalgar'. At the South Kensington Museum (Sheepshanks' gift) are 'Near Cologne', 'A Market Boat on the Scheldt', 'Sands near Boulogne', and (Townshend bequest) 'A Rocky Bay'. Other pictures by him are at the Garrick Club, of which he was an active member. 'Battle of Roveredo' is at the Royal Holloway College, Egham.

Many of his pictures have been engraved (two of them, 'Tilbury Fort' and 'The Castle of Ischia', for the Art Union of London), and book illustrations after sketches are to be found in Heath's 'Picturesque Annual', 1832, &c., Brockedon's 'Road-book from London to Naples', 1835, Stanfield's 'Coast Scenery' 1836, Lawson's 'Scotland Delineated', Mapei's 'Italy', 1847, &c., Marryat's 'Pirate and three Cutters', 1836, and 'Poor Jack', 1840, Dickens' 'Battle of Life', 'Tennyson's 'Poems', 1857, and Tillotson's 'New Waverley Album'.